Reading 2bit files (for fun) - the index

Posted on 2020-09-05 10:59 +0100 in Coding • Tagged with Bioinformatics • 4 min read

As mentioned in the first post, once you've read in the header data for a 2bit file, the next step is to read the index. This is an index into all the different sequences held in the file. Reading the index itself is fairly straightforward.

The index comes right after the header -- so it starts on the 17th byte of the file. Each entry in the index contains three items of information:

| Content | Type | Size | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name length | Integer | 1 byte | How many bytes long the name is |

| Name | String | Varies | Length given by previous field |

| Offset | Integer | 4 bytes | Location in the file of the sequence |

So, in some sort of pseudo-code, you'd read in the index as follows:

index = dict()

for seq = 1 to seq_count // seq_count comes from the header

name_len = (int) read_bytes( 1 )

name = (string) read_bytes( name_len )

offset = (int) read_bytes( 4 )

index[ name ] = offset

end

Note, as mentioned in the first

post, the index will need to

be byte-swapped if the file is in an endian form other than the machine

you're running your code on. How you'd go about this will, of course, vary

from language to language, but the main idea is always going to be the same.

There's a fairly striking downside to this approach though: reading data can often be an expensive (in terms of time) operation -- this is especially true if the data is coming in from a remote machine, perhaps even one that's being accessed over the Internet. As such, it's best if you can make as few "trips" to the file as possible.

With this in mind, the best thing to do is to read the whole index into memory in one go and then process it from there -- the idea being that that's just one trip to the data source. The problem here, however, is that there's nothing in the header or the index that tells you how large the index actually is. What you can do though is work on the worst case scenario (assuming memory will allow). The worst case is fairly easy to handle: it's going to be 1 byte for the name length, plus 255 bytes for the name (the longest possible name), plus 4 bytes for the offset; multiply all that by the number of sequences in the index and you have the worst-case buffer size.

When reading this data in you might also want to ensure you're not going to run off the end of the file (perhaps the names are all quite small and so are the sequences).

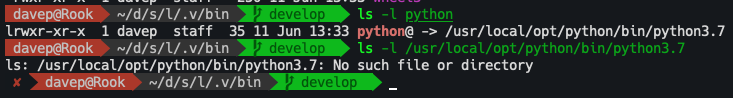

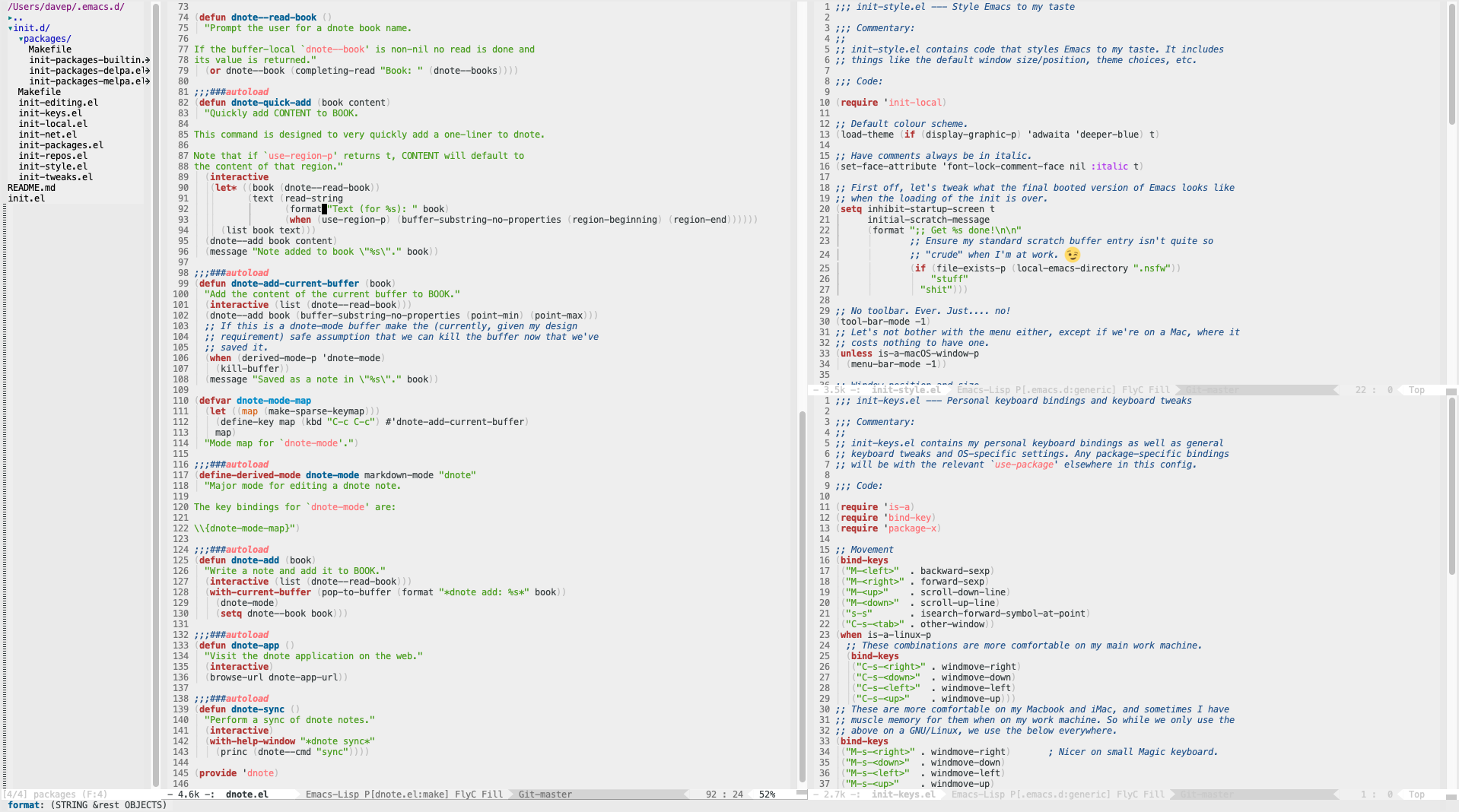

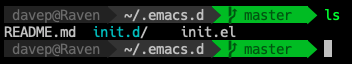

Recently I've been working on a package for Emacs that can read data from 2bit files, so here's the core code for reading in the index:

(defun 2bit--read-index (source)

"Read the sequence index from SOURCE.

As a side effect `2bit-data-pos' of SOURCE will move."

(cl-loop

;; The index will be a hash of sequence names, with the values being the

;; offsets within the file.

with index = (make-hash-table :test #'equal)

;; We could read each name/value pair one by one, but because we're doing

;; this within Emacs, which means making a temp buffer for every read,

;; that could get pretty expensive pretty fast. So instead we'll read the

;; index data in in one go. However, there is no easy-to-calculate size

;; for the index. The best we can do is calculate the worst case size. So

;; let's do that. The worst case size is the maximum size of the name of

;; a sequence (255), plus the size of the byte that tells us the name

;; (1), plus the size of the word that is the offset in the file (4).

with buffer = (2bit--read source (* (2bit-data-sequence-count source) (+ 255 1 4)))

;; For every sequence in the file...

for n from 1 to (2bit-data-sequence-count source)

;; Calculate the position within the buffer for this loop around. Note

;; that the skip is the last position plus 1 for the size byte plus the

;; size plus the length of the offset word.

for pos = 0 then (+ pos 1 size 4)

;; Get the length of the name of the sequence.

for size = (aref buffer pos)

;; Pull out the name itself.

for name = (substring buffer (1+ pos) (+ pos 1 size))

;; Pull out the offset.

for offset = (2bit--word-from-bytes source (substring buffer (+ pos 1 size) (+ pos 1 size 4)))

;; Collect the offset into the hash.

do (setf (gethash name index) offset)

;; Once we're all done.... return the index.

finally return index))

This code does what I mention above: it grabs enough data into a buffer in

one go that I'll have the whole index in memory to pull apart, and then I

work with the in-memory copy. The index is added to a hashing dictionary.

Note that, in this case, I don't actually do the test for running off the

end of the file because at the heart of the file reading code is

insert-file-contents-literally

and it doesn't error if you request too much.

With that done you'll have a list of all the sequences in the file. The next part, which will come in the next post, is the properly tricky part: the decoding of the sequence data itself.