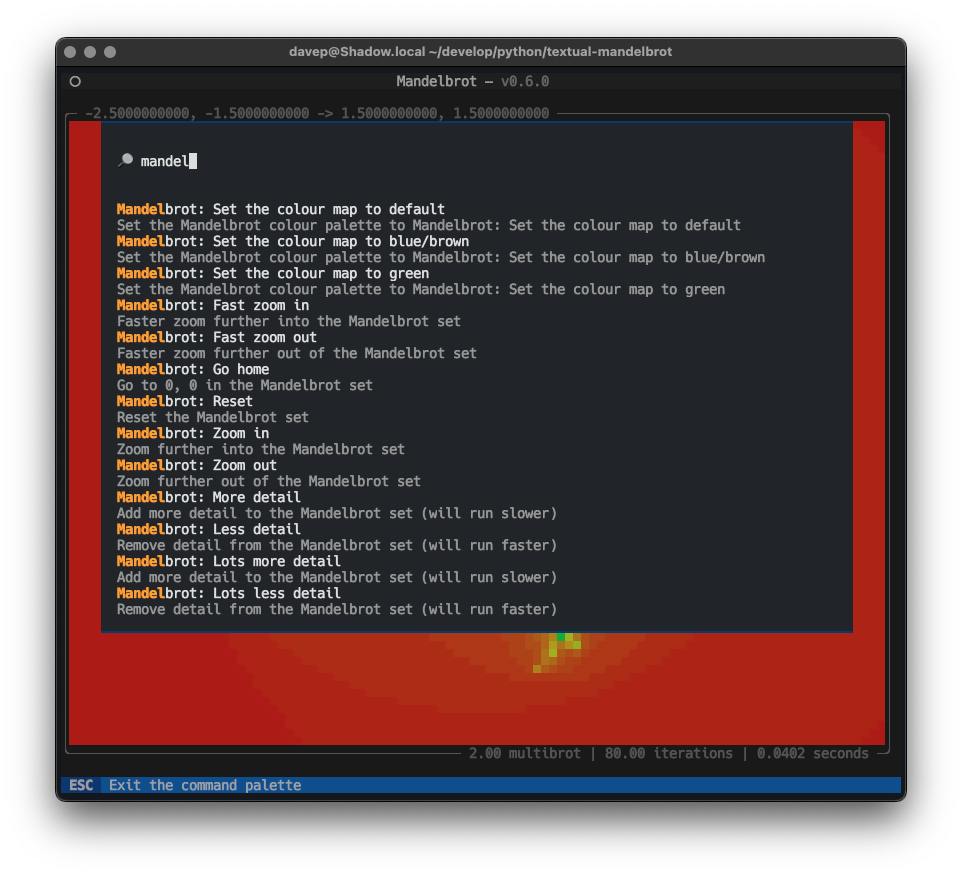

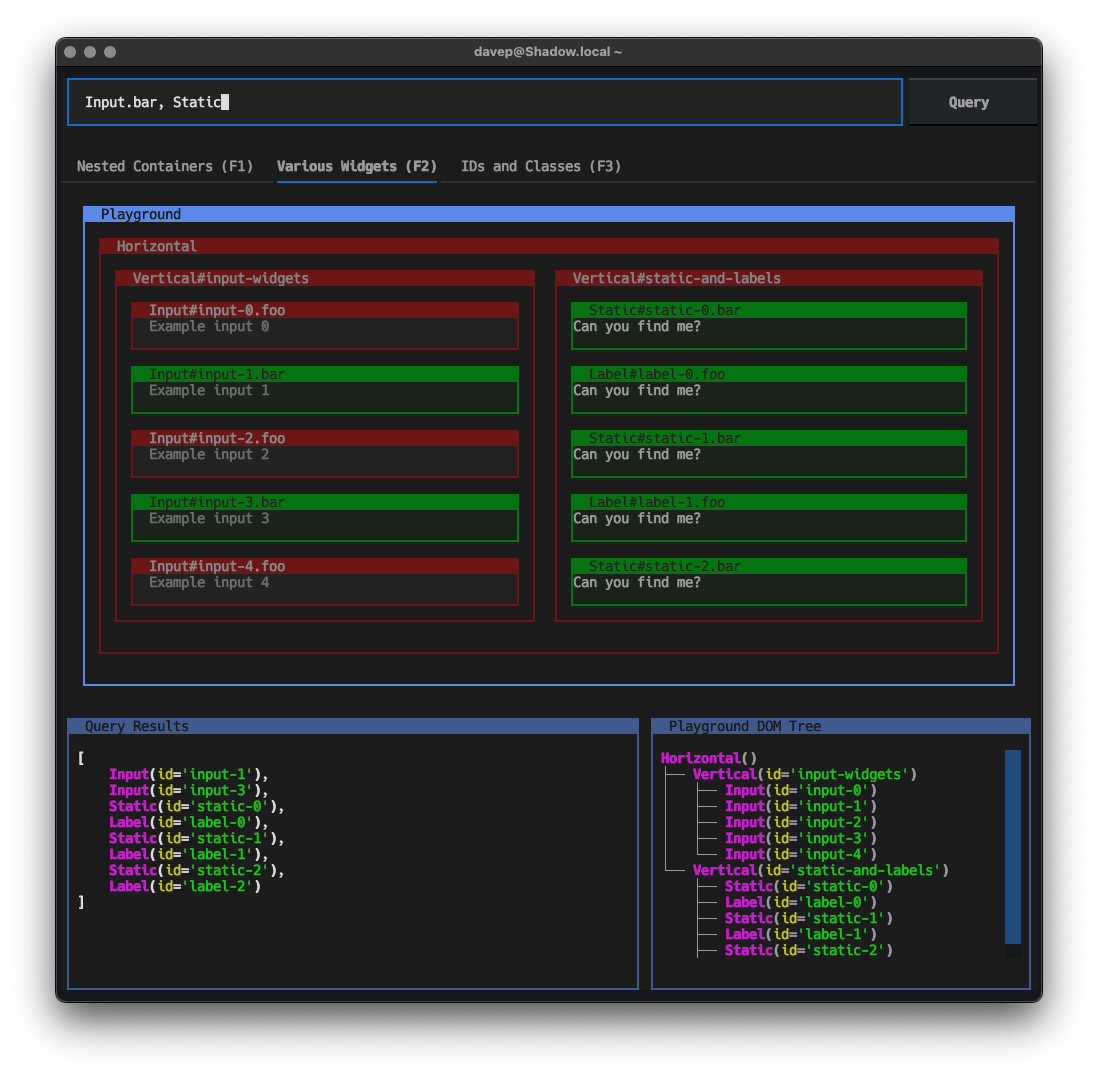

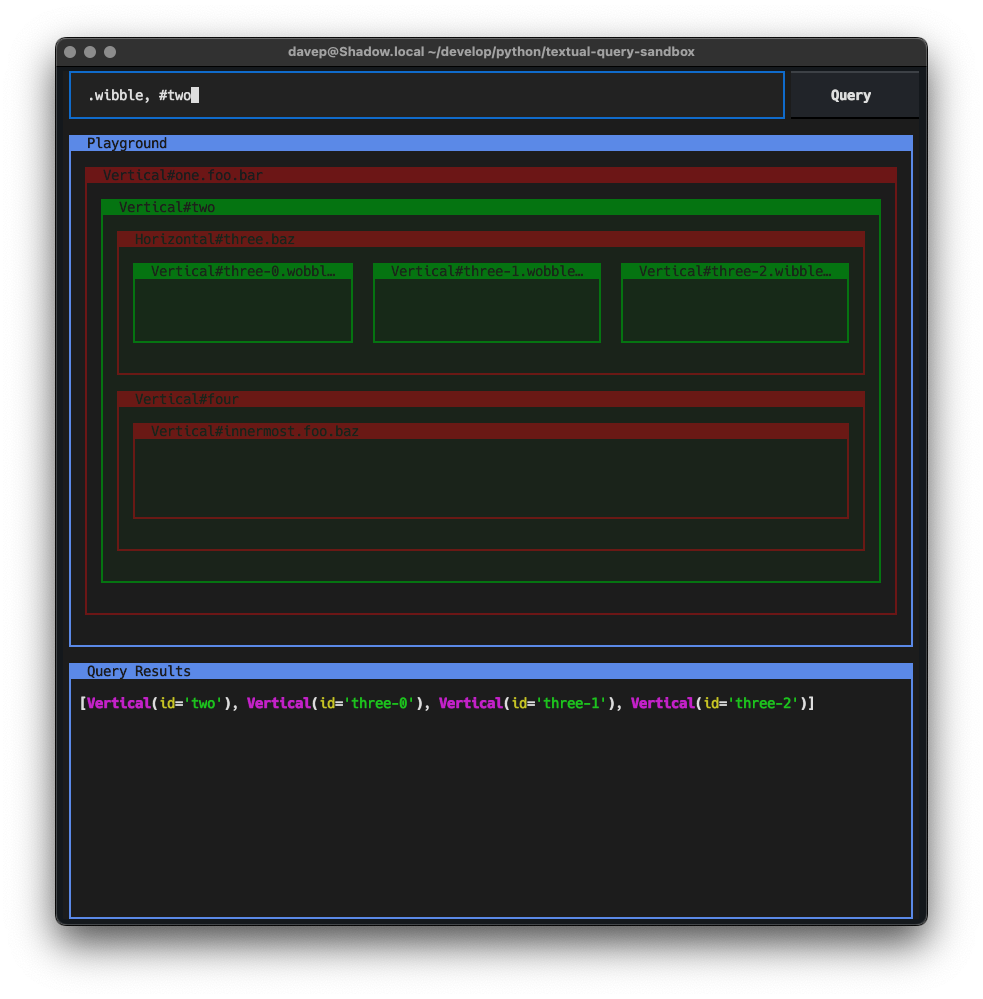

Last week I was wrestling with some Textual code, trying to get something to lay out on the screen "just so". On the whole this isn't too tricky at all, and for those times where it might feel tricky there's some advice available on how to go about it. But in this case I was trying to do a couple of "on the edge" things and one thing I really needed to know was what particular part of the display was being "caused" by what container or widget1.

Now, at the moment anyway, Textual doesn't have a full-blown devtools with all the bells and whistles; not like in your average web browser. It does have a devtools, but not with all the fancy DOM-diving stuff the above would have needed.

What I needed was the equivalent of print-debugging but with a

point-and-ask interface. Now, I actually do often do print-debugging

with Textual apps only I use

notify;

this time though notify wasn't going to cut it.

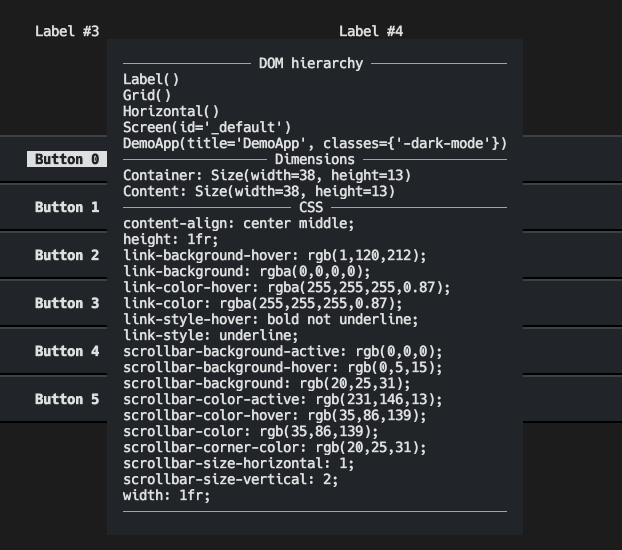

I needed something that would let me point at a widget and say "show me stuff about this". Something that happens when the mouse hovers over a widget. Something like... a tooltip!

So that was easy:

def on_mount(self) -> None:

for widget in [self, *self.query("*")]:

widget.tooltip = "\n".join(

f"{node!r}" for node in widget.ancestors_with_self

)

Suddenly I could hover my mouse over a bit of space on the screen and get a "traceback" of sorts for what "caused" it.

I posted this little hack to #show-and-tell on the Discord

server and someone mentioned it would be

handy if it also showed the CSS for the widget too. That was simple enough

because every widget has a styles.css property that is the CSS for the

widget, as a string.

After that I didn't think much more about it; until today.

Looking back, one thing I realised is that adding the CSS information

on_mount wasn't quite good enough, as it would only show me the state of

CSS when the mount happened, not at the moment I inspect the widget. I

needed the tooltip to be dynamic.

Thing is... Textual tooltips can't be functions (which would be the obvious approach to make it dynamic); so there was no way to get this on-the-fly behaviour I wanted.

Except there was! The type of

tooltip

is RenderableType. So that means I could assign it an object that is a

Rich renderable; that in turn means I could write a __rich__ method for a

class that wraps a widget and then reports back what it can see every time

it's called.

In other words, via one step of indirection, I could get the "call a function each time" approach I was after!

It works a treat too.

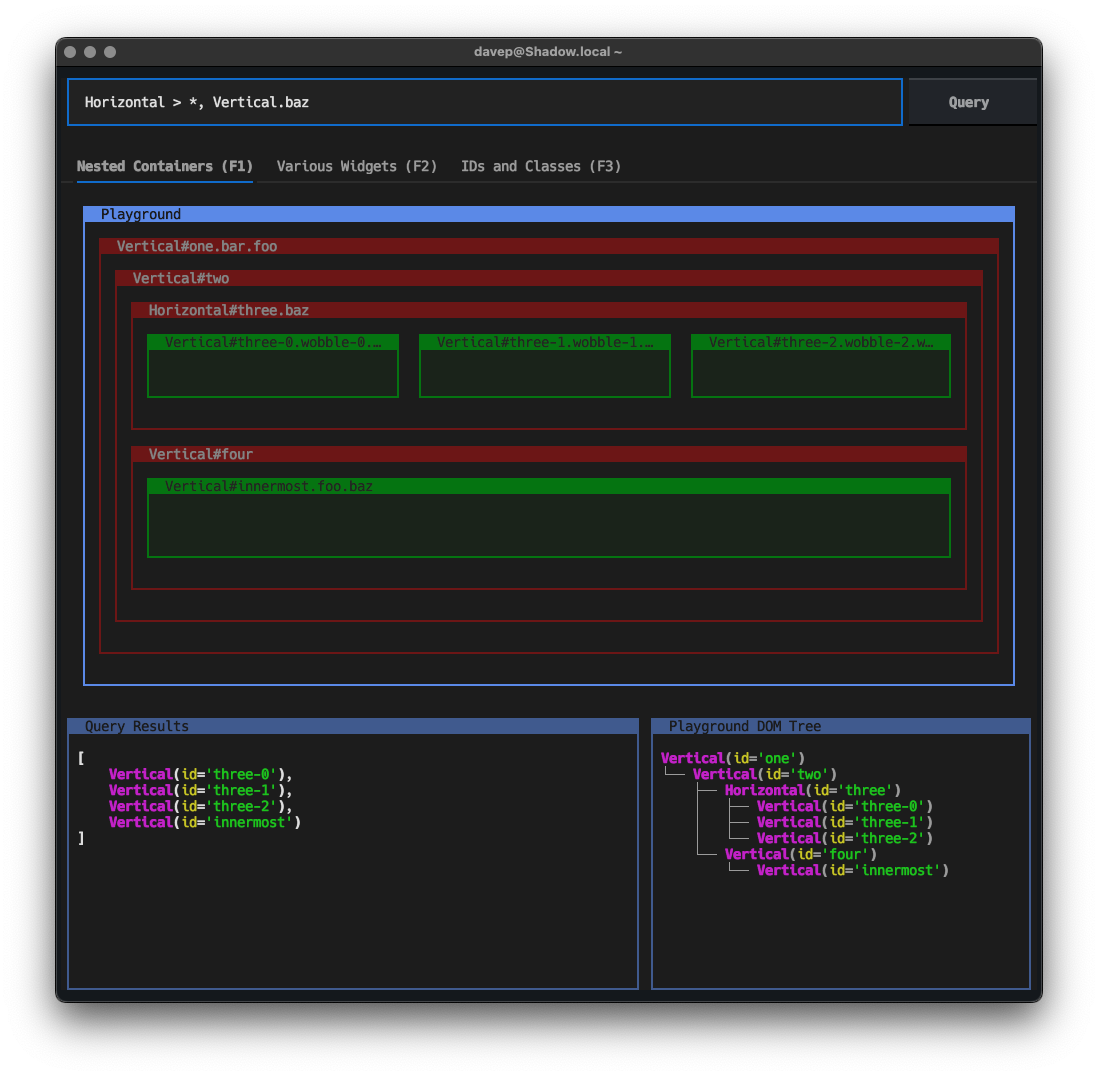

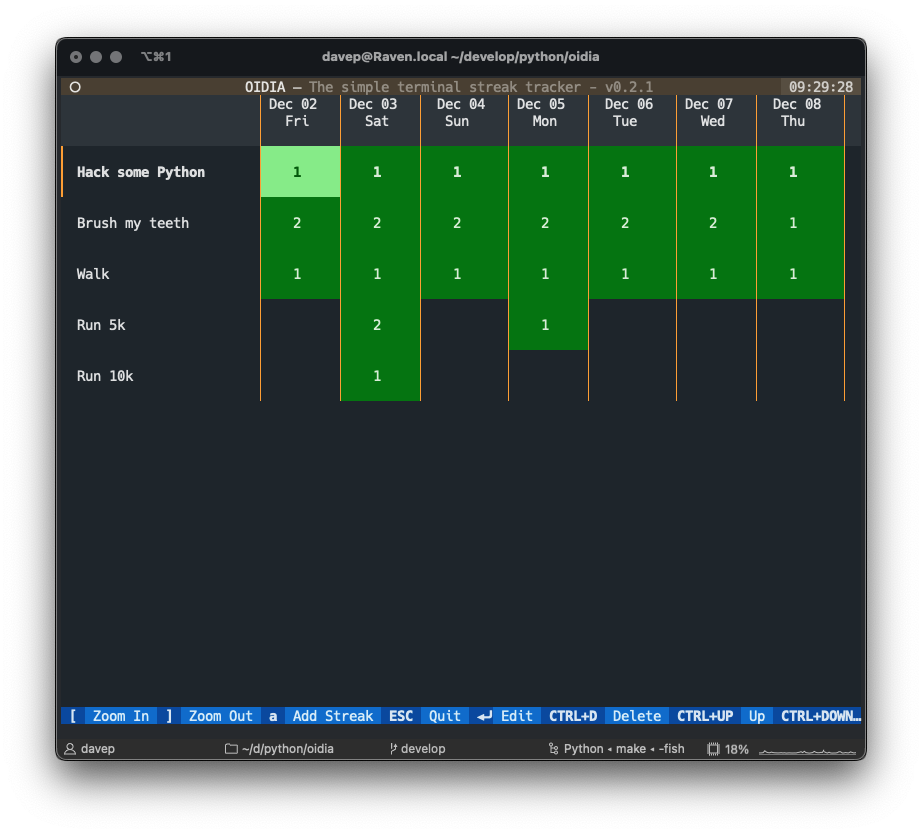

All of which is a long-winded way of saying I now have a print-debug-level

DOM inspector tool for when I'm building applications with Textual:

If this sounds handy to you, you can grab the code too. Install it into your

development environment with pip:

$ pip install textual-dominfo

and then attach it to your app or screen or some top-level widget you're

interested in via on_mount; for example:

def on_mount(self) -> None:

from textual_dominfo import DOMInfo

DOMInfo.attach_to(self)

and then hover away with that mouse cursor and inspect all the things! Whatever you do though, don't make it part of your runtime, and don't keep it installed; just make it a development dependency.

The source can be found over on GitHub and the package is, as mentioned above, over on PyPi.

-

ObPedant: Containers are widgets, but it's often helpful to make a distinction between widgets that exist just to control the layout of the widgets inside them, and widgets that exist to actually do or show stuff. ↩