Another itch to scratch

As I mentioned yesterday, I've been a happy

user of Pelican for a couple or so years now, but

every so often there's a little change or tweak I'd like to make that

requires diving deeper into the templates and the like and... I go "eh,

I'll look at it some time soon". Another thought that often goes through my

head at those times is "I should build my own static site generator that

works exactly how I want" -- because really any hacker with a blog has to

do that at some point.

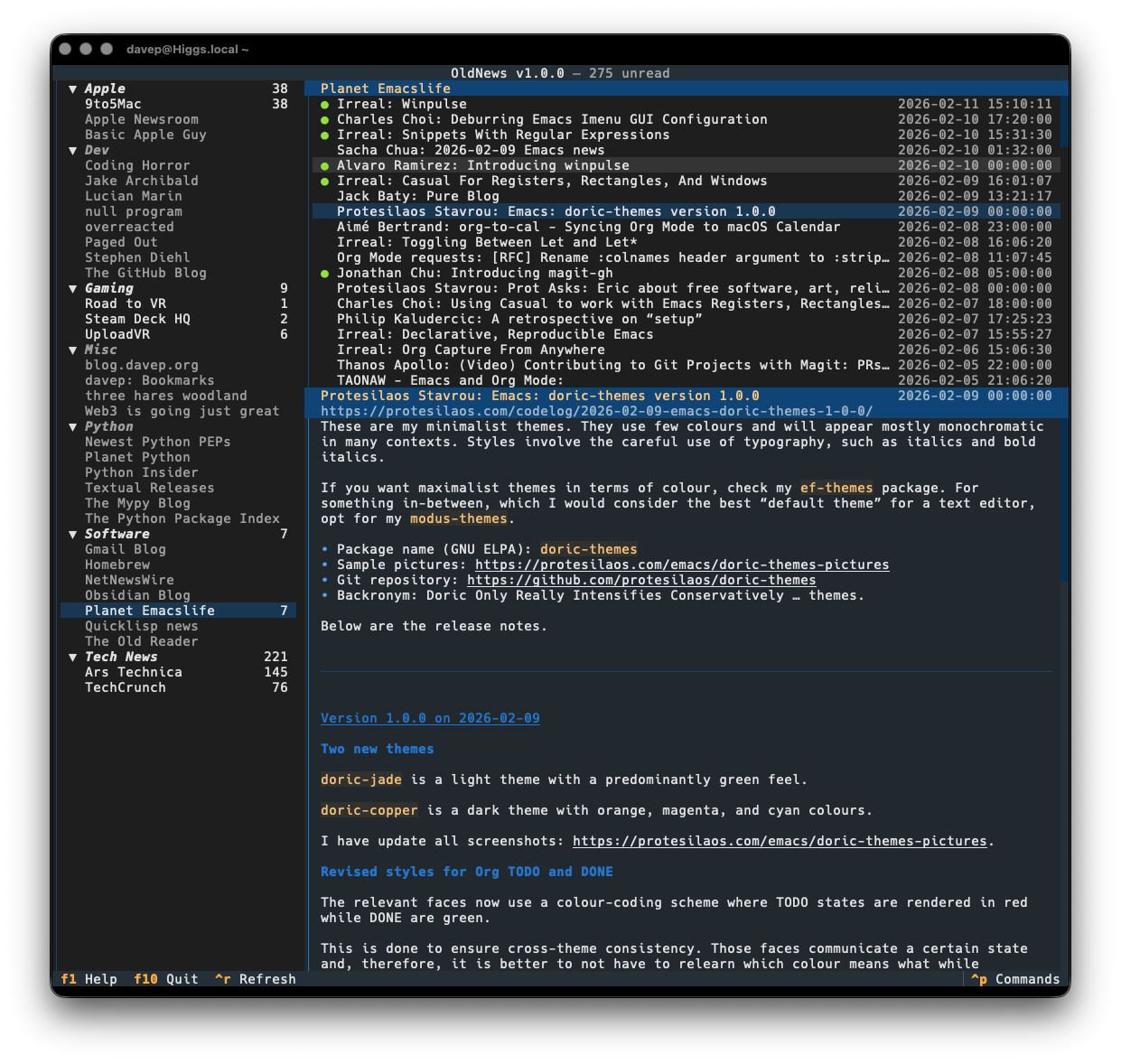

Meanwhile... I've had free access to GitHub

Copilot attached to my GitHub

account for some time now, and I've hardly used

it. At the same time -- the past few months especially -- I've been watching

the rise of agents as coding tools, as well as the rise of advocates for

them. Worse still, I've seen people I didn't expect to be advocates for

giving up on coding turning to these tools and suddenly writing rationales

in favour of them.

So, suddenly, the idea popped into my head: I should write my own static

site generator that I'll use for my blog, and I should try and use GitHub

Copilot to write 100% of the code, and documentation, and see how far I get.

In doing so I might firm up my opinions about where we're all going with

this.

The requirements were going to be pretty straightforward:

- It should be a static site generator that turns Markdown files into a

website.

- It should be blog-first in its design.

- It should support non-blog-post pages too.

- It should be written in Python.

- It should use Jinja2 for templates.

- It should have a better archive system than I ever got out of my Pelican

setup.

- It should have categories, tags, and all the usual metadata stuff you'd

expect from a site where you're going to share content from.

Of course, the requirements would drift and expand as I went along and I had

some new ideas.

Getting started

To kick things off, I created my repo,

and then opened Copilot and typed out a prompt to get things going. Here's

what I typed:

Build a blog-oriented static site generation engine. It should be built in

Python, the structure of the repository should match that of my preferences

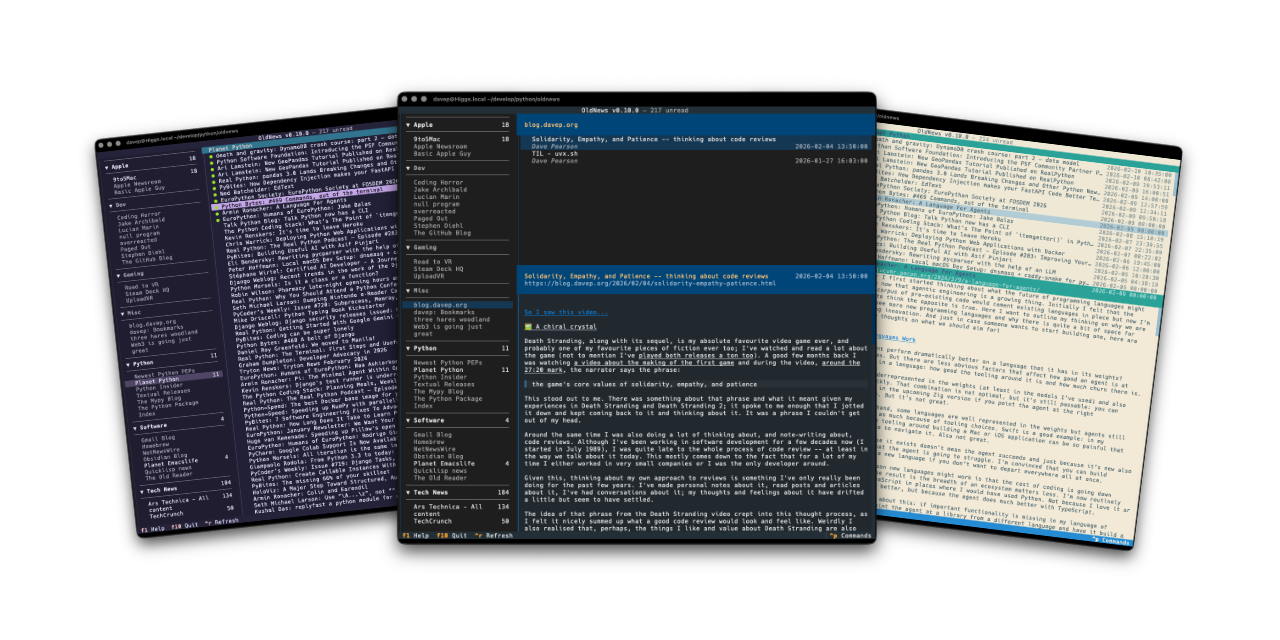

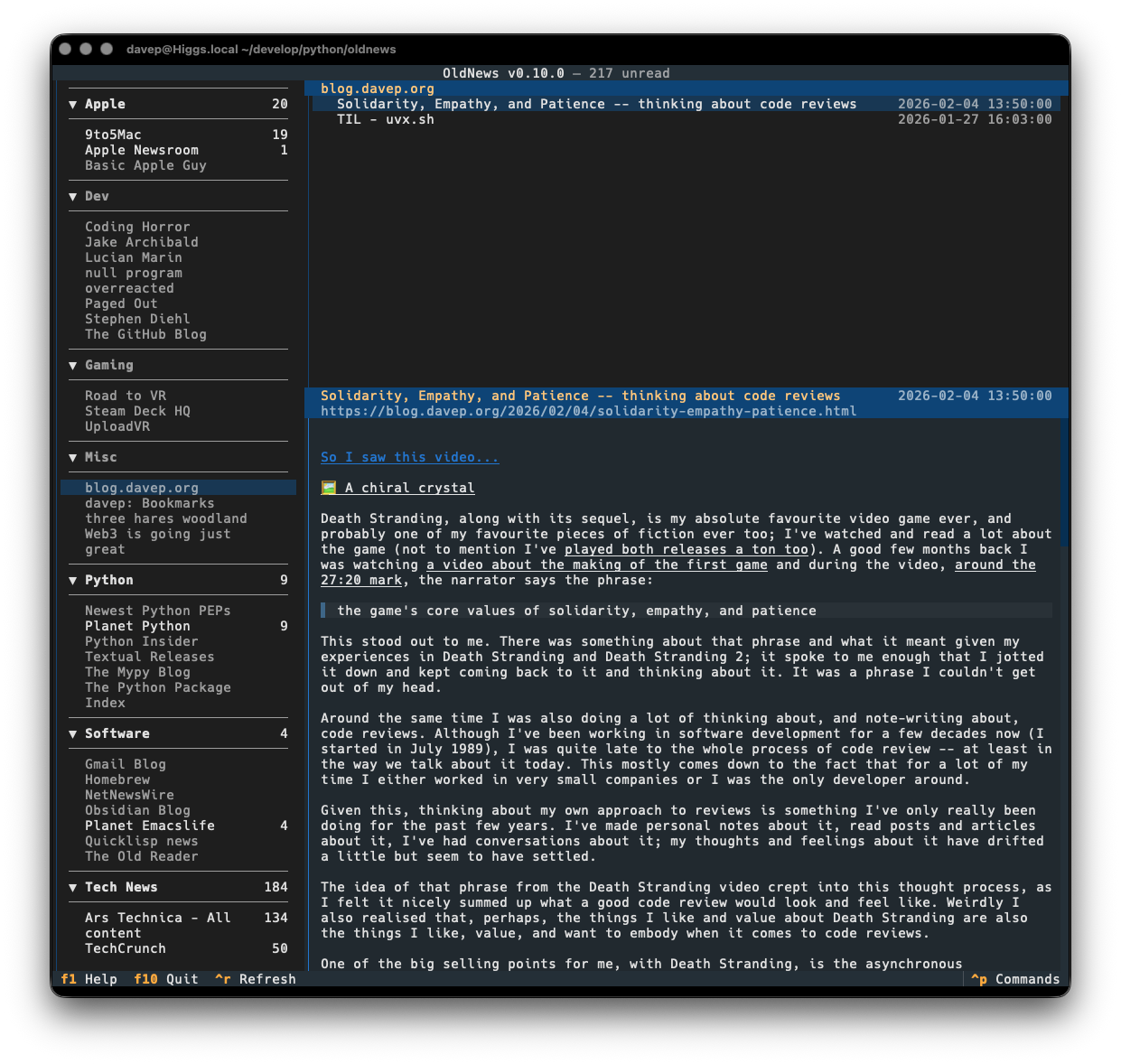

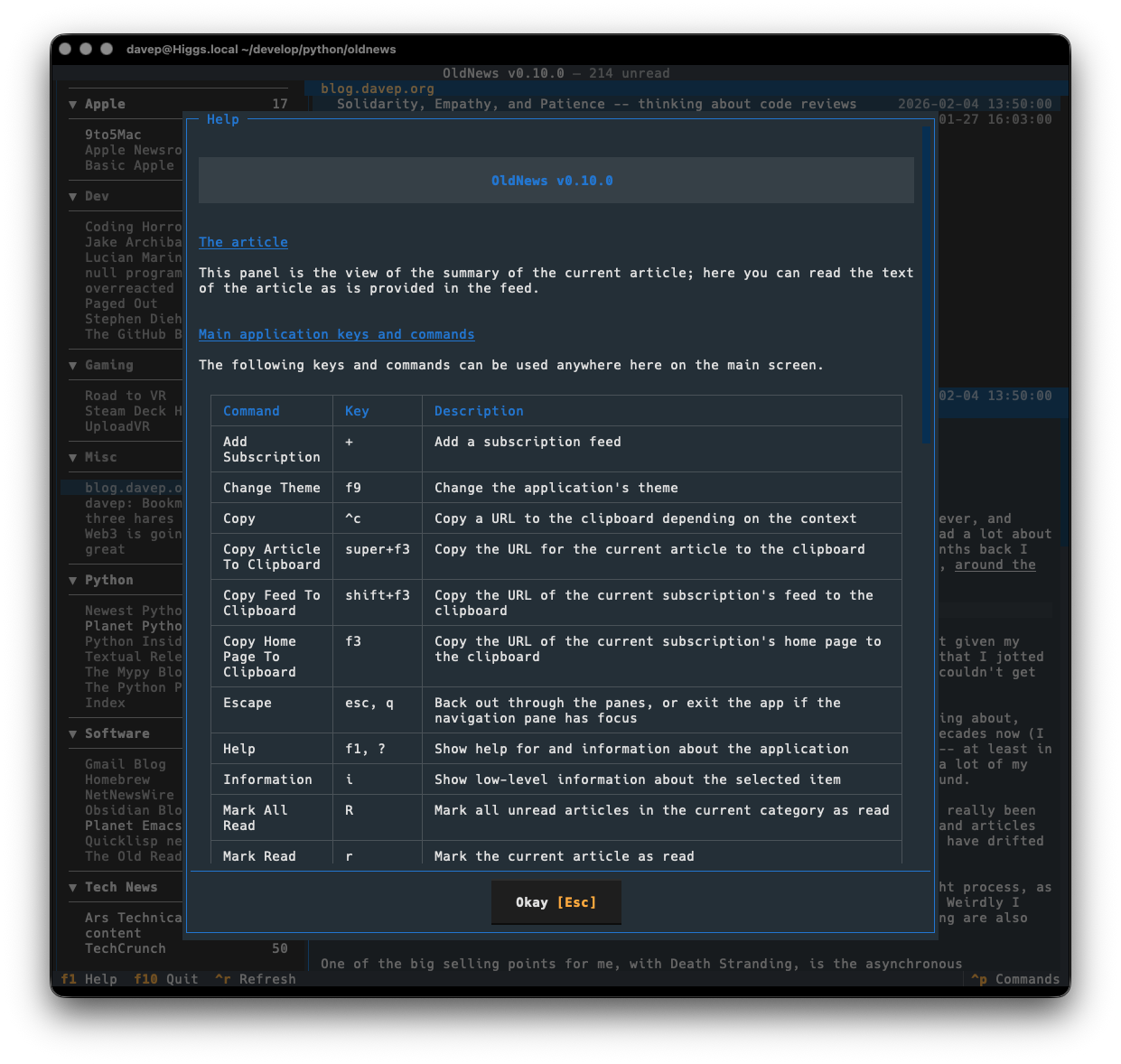

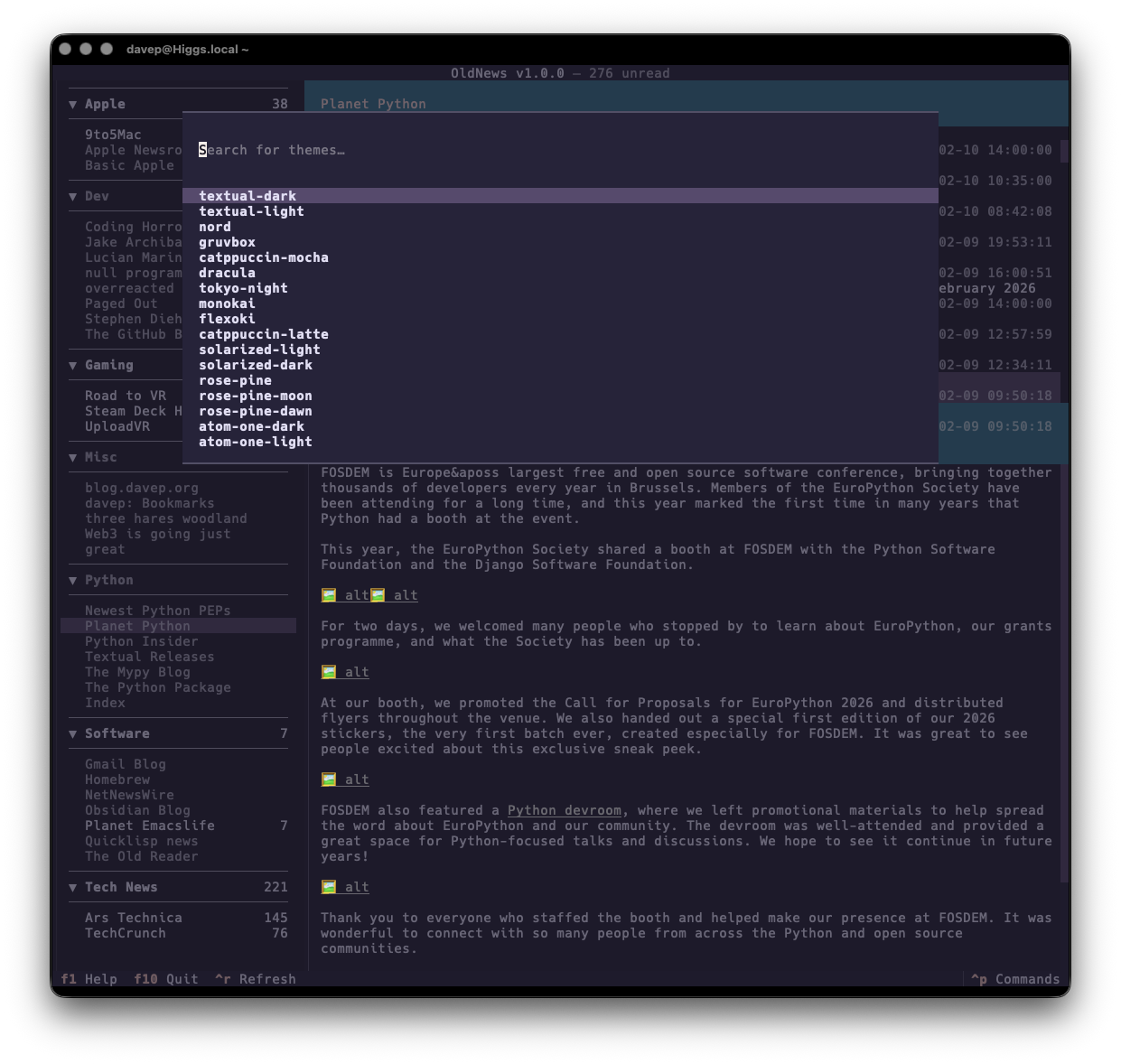

for Python projects these days (see https://github.com/davep/oldnews and

take clues from the makefile; I like uv and ruff and Mypy, etc).

Important features:

- Everything is written in markdown

- All metadata for a post should come from frontmatter

- It should use Jinja2 for the output templates

As you can see, rather than get very explicit about every single detail, I

wanted to start out with a vague description of what I was aiming for. I did

want to encourage it to try and build a Python repository how I normally

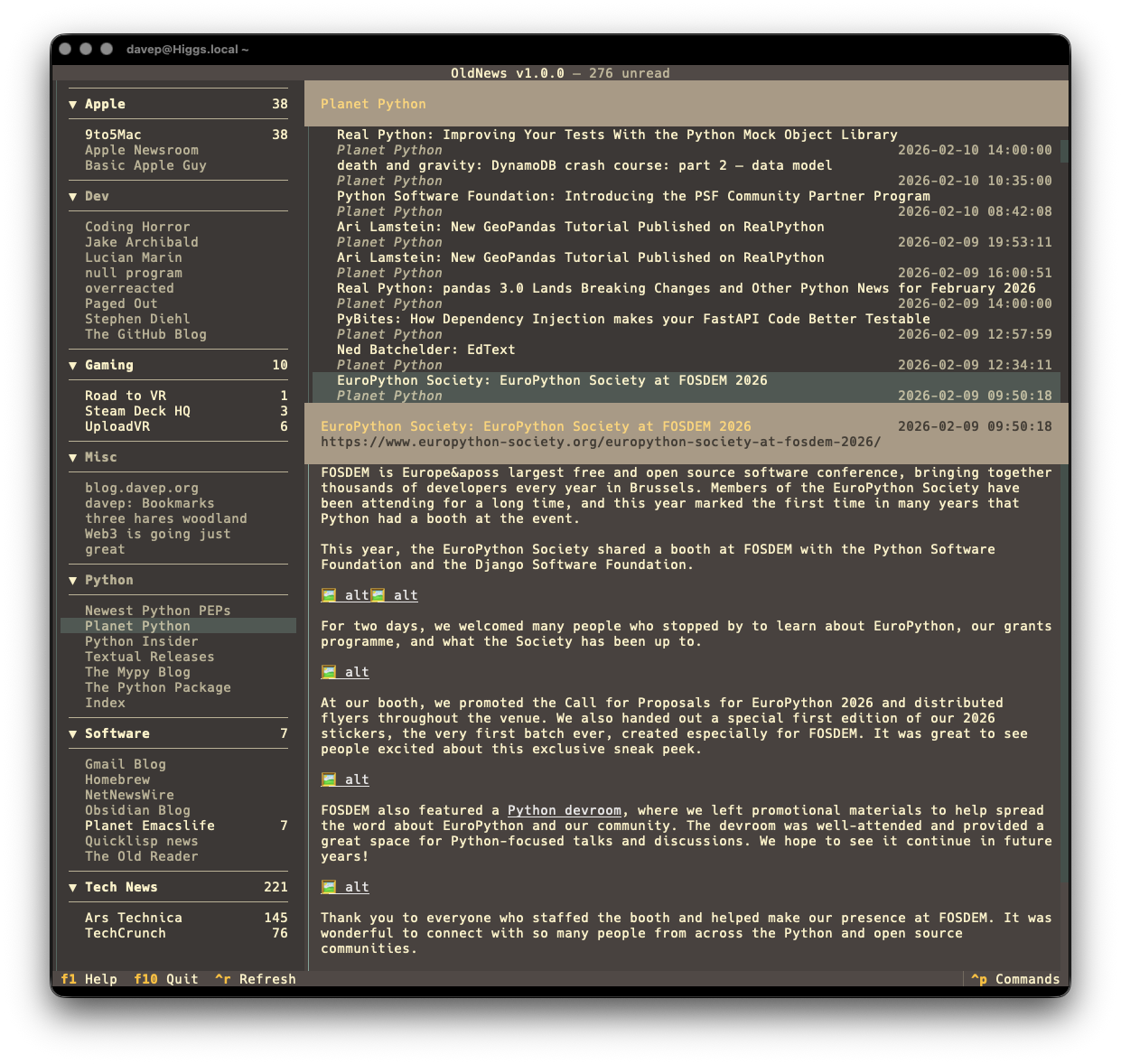

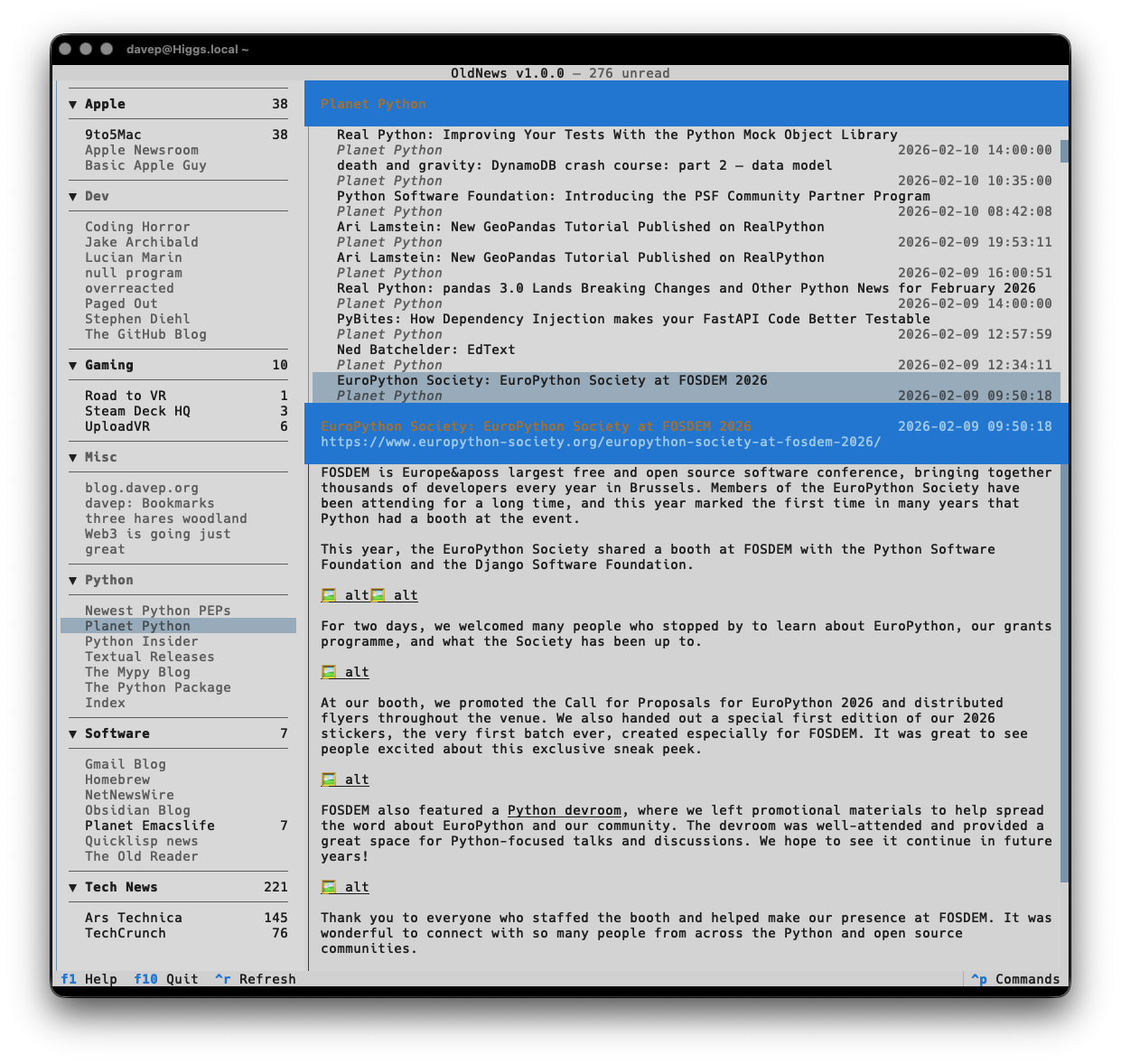

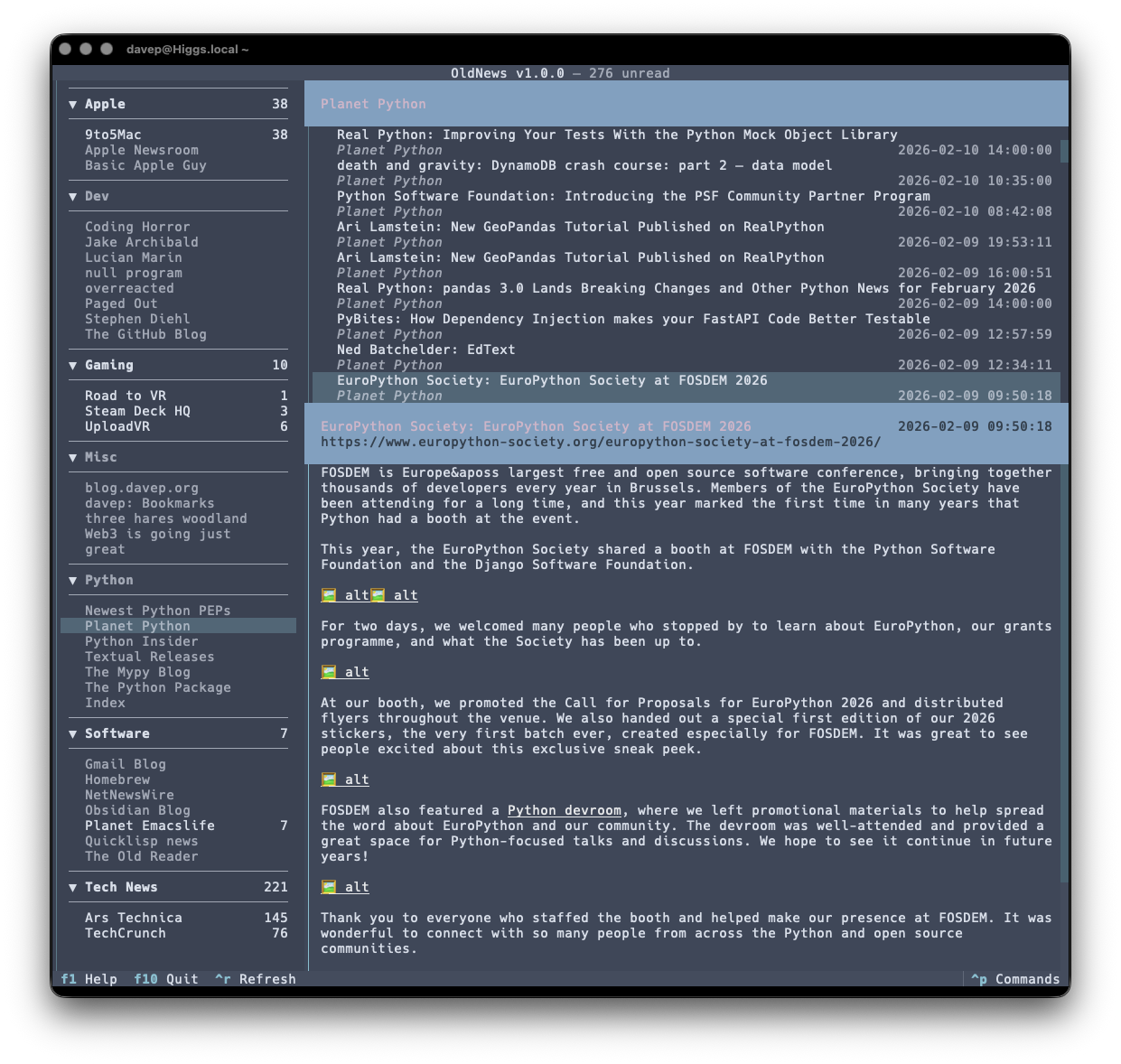

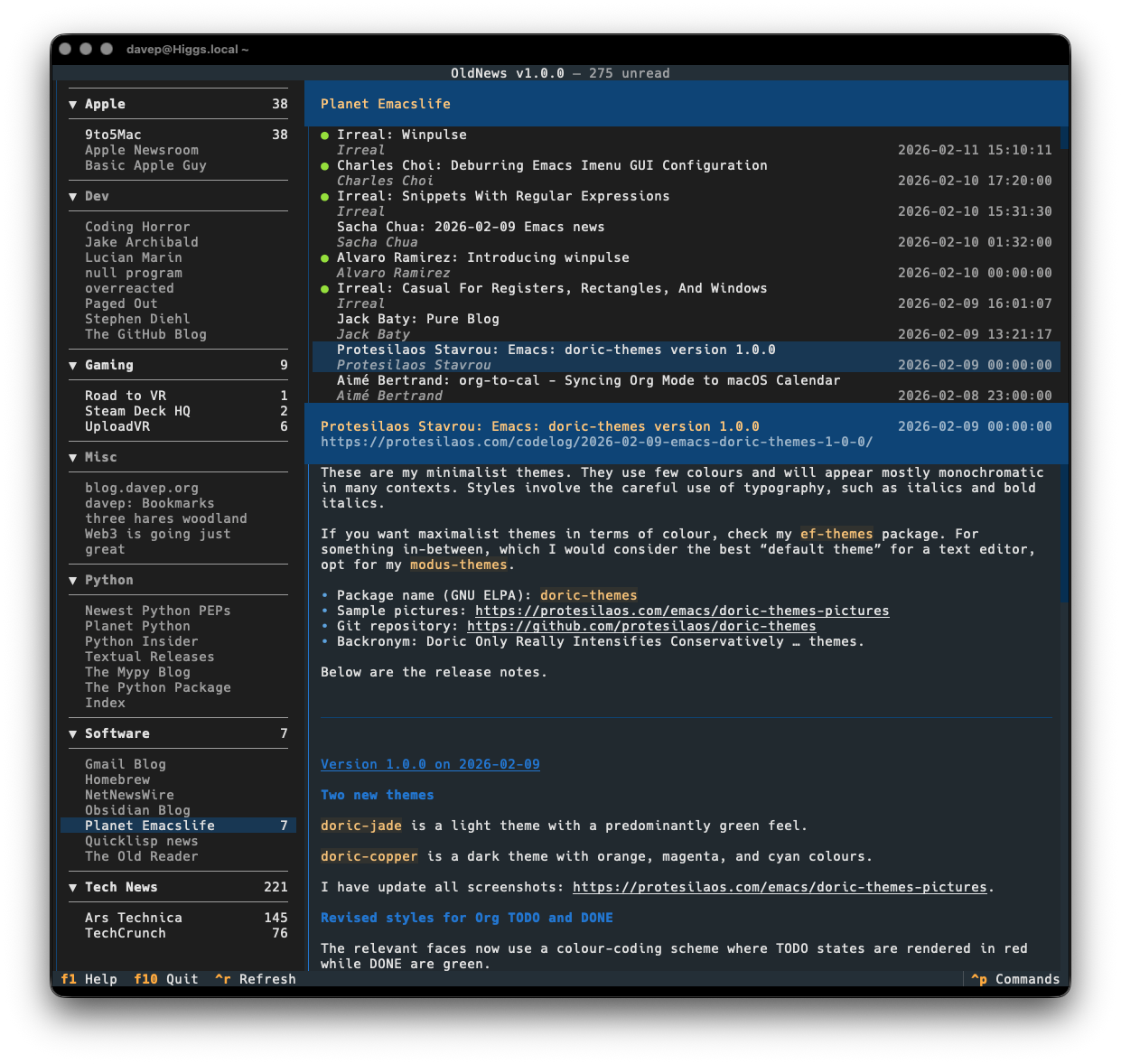

would, so I pointed it at OldNews in the

hope that it might go and comprehend how I go about things; I also

doubled-down in the importance of using uv and mypy.

The result of this was... actually

impressive. As you'll see in that

PR, to get to a point where it could be merged, there was some

back-and-forth with Copilot to add things I hadn't thought of initially, and

to get it to iron out some problems, but for the most part it delivered what

I was after. Without question it delivered it faster than I would have.

Some early issues where I had to point out problems to Copilot included:

- The order of posts on the home page wasn't obvious to me, and absolutely

wasn't reverse chronological order.

- Footnotes were showing up kinda odd.

- The main index for the blog was showing just posts titles, not the full

text of the article as you'd normally expect from a blog.

Nothing terrible, and it did get a lot of the heavy lifting done and done

well, but it was worth noting that a lot of dev-testing/QA needed to be done

to be confident about its work, and doing this picked up on little details

that are important.

An improvement to the Markdown

As an aside: during this first PR, I quickly noticed a problem where I was

getting this error when generating the site from the

Markdown:

Error generating site: mapping values are not allowed in this context

in "<unicode string>", line 3, column 15

I just assumed it was some bug in the generated code and left Copilot to

work it out. Instead it came back and educated me on something: I actually

had bad YAML in the frontmatter of some of my

posts!

This, by the way, wouldn't be the last time that Copilot found an issue with

my input Markdown and so, having used it, improved my blog.

A major feature from a simple request

Another problem I ran into quickly was that previewing the generated site

wasn't working well at all; all I could do was browse the files in the

filesystem. So, almost as an offhand comment, in the initial PR, I

asked:

Can we get a serve mode please so I can locally test the site?

Just like that, it went off and wrote a whole server for the

project.

While the server did need a lot of extra work to really work well, the

initial version was good enough to get me going and to iterate on the

project as a whole.

The main workflow

Having kicked off the project and having had some success with getting

Copilot to deliver what I was asking for, I settled into a new but also

familiar workflow. Whereas normally, when working on a personal project,

I'll write an issue for myself, at some point pick it up and create a PR,

review and test the PR myself then merge, now the workflow turned into:

- Write an issue but do so in a way that when I assign it to Copilot it has

enough information to go off and do the work.

- Wait for Copilot to get done.

- Review the PR, making change requests etc.

- Make any fixes that are easier for me to fix by hand that describe to

Copilot.

- Merge.

In fact, the first step had some sub-steps to it too, I was finding. What I

was doing, more than ever, was writing issues like I'd write sticky notes:

with simple descriptions of a bug or a new feature. I'd then come back to

them later and flesh them out into something that would act as a prompt for

Copilot. I found myself doing this so often I ended up adding a "Needs

prompt" label to my usual set of issue

labels.

All of this made for an efficient workflow, and one where I could often get

on with something else as Copilot worked on the latest job (I wasn't just

working on other things on my computer; sometimes I'd be going off and doing

things around the house while this happened), but... it wasn't fun. It was

the opposite of what I've always enjoyed when it comes to building software.

I got to dream up the ideas, I got to do the testing, I got to review the

quality of the work, but I didn't get to actually lose myself in the flow

state of coding.

One thing I've really come to understand during those 5 days of working on

BlogMore was I really missed getting lost in the flow state. Perhaps it's

the issue to PR to review to merge cycle I used that amplified this, perhaps

those who converse with an agent in their IDE or in some client application

keep a sense of that (I might have to try that approach out), but this feels

like a serious loss to me when it comes to writing code for personal

enjoyment.

The main problems

I think it's fair to say that I've been surprised at just how well Copilot

understood my (sometimes deliberately vague) requests, at how it generally

managed to take some simple plain English and turn it into actual code that

actually did what I wanted and, mostly, actually worked.

But my experiences over the past few days haven't been without their

problems.

The confidently wrong problem

Hopefully we all recognise that, with time and experience, we learn where

the mistakes are likely to turn up. Once you've written enough code you've

also written plenty of bugs and been caught out by plenty of edge-cases that

you get a spidey-sense for trouble as you write code. I feel that this kind

of approach can be called cautiously confident.

Working with Copilot, however, I often ran into the confidently wrong

issue. On occasion I found it would proudly request review for some

minor bit of work, proclaiming that it had done the thing or solved the

problem, and I'd test it and nothing had materially changed. On a couple of

occasions, when I pushed back, I found it actually doubting my review before

finally digging in harder and eventually solving the issue.

I found that this took time and was rather tiring.

There were also times where it would do the same but not directly in respect

to code. One example I can think of is when it was confident that Python

3.14 was still a pre-release Python as of February 2026 (it

isn't).

This problem alone concerns me; this is the sort of thing where people

without a good sense for when the agent is probably bullshitting will get

into serious trouble.

The tries-too-hard problem

A variation on the above problem works the other way: on at least one

occasion I found that Copilot tried too hard to fix a problem that wasn't

really its to fix.

In this case I was asking it to tidy up some validation issues in the RSS

feed data. One of the main

problems was root-relative URLs being in the content of the feed; for that

they needed to be made absolute URLs. Copilot did an excellent job of fixing

the problem, but one (and from what I could see only one) relative URL

remained.

I asked it to take a

look

and it took a real age to work over the issue. To its credit, it dug hard

and it dug deep and it got to the bottom of the problem. The issue here

though was it tried too hard because, having found the cause of the problem

(a typo in my original Markdown, which had always existed) it went right

ahead and built a workaround for this one specific broken link.

Now, while I'm a fan of Postel's

law, this is taking

things a bit too far. If this was a real person I'd tasked with the job I

would have expected and encouraged them to come back to me with their

finding and say "dude, the problem is in your input data" and I'd have

fixed my original Markdown.

Here though it just went right ahead and added this one weird edge case as

something to handle.

I think this is something to be concerned about and to keep an eye on too. I

feel there's a danger in having the agent rabbit-hole a fix for a problem

that it should simply have reported back to me for further discussion.

The never-pushes-back problem

Something I did find unsurprising but disconcerting was Copilot's

unwillingness to push back, or at least defend its choices. Sometimes it

would make a decision or a change and I'd simply ask it why it had done it

that way, why it had made that choice. Rather than reply with its reasoning

it would pretty much go "yeah, my bad, let me do it a way you're probably

going to find more pleasing".

A simple example of this is one time when I saw some code like this:

@property

def some_property(self) -> SomeValue:

from blogmore.utils import some_utility_function

...

I'm not a fan of imports in the body of methods unless there's a

demonstrable performance reason. I asked Copilot why it had made this choice

here and its reply was simply to say it had gone ahead and changed the code,

moving the import to the top of the module.

I see plenty of people talk about how working with an agent is like

pair-programming, but I think it misses out on what's got to be the biggest

positive of that approach: the debate and exchange of ideas. This again

feels like a concern to be mindful of, especially if someone less

experienced is bringing code to you where they've used an agent as their

pair buddy.

The overall impression

Now I'm at the end of the process, and using the result of this experiment

to write this post, I feel better informed about what these tools offer,

and the pitfalls I need to be mindful of. Sometimes it wasn't a terrible way

of working. For example, on the first day I started with this, at one point

on a chilly but sunny Sunday afternoon, I was sat on the sofa, MacBook on

lap, guiding an AI to write code, while petting the cat, watching the birds

in the garden enjoy the content of the feeder, all while chatting with my

partner.

That's not a terrible way to write code.

On the other hand, as I said earlier, I missed the flow state. I love

getting lost in code for a few hours and this is not that. I also found the

constant loop of prompt, wait, review, test, repeat, really quite

exhausting.

As best as I can describe it: it feels like the fast food of software

development. It gets the job done, it gets it done fast, but it's really not

fulfilling.

At the end of the process I have a really useful tool, 100% "built with AI",

under my guidance, which lets me actually be creative and build things I

do create by hand. That's not a bad thing, I can see why this is appealing

to people. On the other hand the process of building that tool was pretty

boring and, for want of a better word... soulless.

Conclusion

As I write this I have about 24 hours of access to GitHub Copilot Pro left.

It seems this experiment used up my preview time and triggered a "looks

like you're having fun, now you need to decide if you want to buy it"

response. That's fair.

So now I'm left trying to decide if I want to pay to keep it going. At the

level I've been using it at for building BlogMore it looks like it costs

$10/mth. That actually isn't terrible. I spend more than that on other

hobbies and other forms of entertainment. So, if I can work within the

bounds of that tier, it's affordable and probably worth it.

What I'm not sure about yet is if I want to. It's been educational, I can

100% see how and where I'd use this for work (and would of course expect an

employer to foot the bill for it or a similar tool), and I can also see how

and where I might use it to quickly build a personal-use tool to enable

something more human-creative.

Ultimately though I think I'm a little better informed thanks to this

process, and better aware of some of the wins people claim, and also better

informed so that I can be rightly incredulous when faced with some of the

wilder claims.

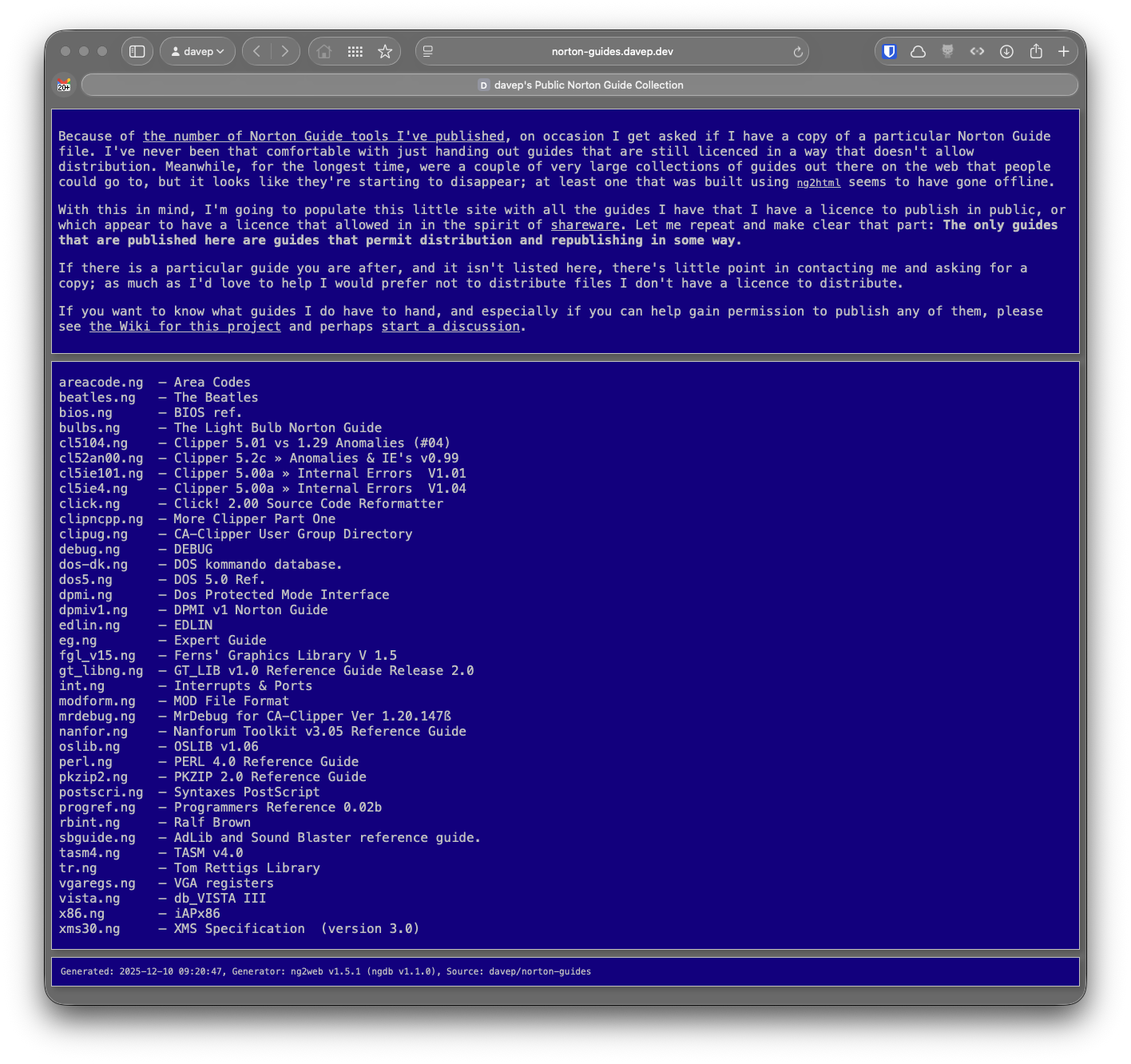

Also, it'll help put some of my

reading

into perspective.