I've just made a wee update to

textual-fspicker, my dialog

library for Textual which adds FileOpen,

FileSave and SelectDirectory dialogs. There's no substantial change to

the workings of the library itself, but I have added something it's been

lacking for a long time: documentation!

Well... that's not quite true, it's always had documentation. I'm an avid

writer of Python docstrings and I make a point of always writing them for

every class, function, method or global value as I write the code. As such

the low-level "API" documentation has always been sat there ready to be

published somehow, eventually.

Meanwhile the description for how to use the library was mostly a pointer to

some example code inside the README. Not ideal, and something I really

wanted to improve at some point.

Given I'm still on a bit of a coding spree in my spare time, I finally

decided to get round to using the amazing

mkdocstrings, in conjunction with

mkdocs, to get some better documentation up an

running.

The approach I decided to take with the documentation was to have a page

that gave some general information on how to use the

library and then also

generate low-level documentation for the all the useful content of the

library from the

docstrings.

While latter isn't really useful to anyone wanting to use the library in

their own applications, it could be useful to anyone wanting to understand

how it hangs together at a lower-level, perhaps because they want to

contribute to or extend the library in some way.

While writing some of the general guide took a bit of work, of course, the

work to get the documentation up and running and generating was simple

enough. The effort comes down to 3 rules in the

Makefile

for the project:

##############################################################################

# Documentation.

.PHONY: docs

docs: # Generate the system documentation

$(mkdocs) build

.PHONY: rtfm

rtfm: # Locally read the library documentation

$(mkdocs) serve

.PHONY: publishdocs

publishdocs: docs # Set up the docs for publishing

$(run) ghp-import --push site

The rtfm target is useful for locally-serving the documentation so I can

live preview as I write things and update the code. The publishdocs target

is used to create and push a gh-pages branch for the repository, resulting

in the documentation being hosted by GitHub.

A wee problem

NOTE: I've since found out there's an easier way of fixing the issue.

This is, however, where I ran into a wee problem. I noticed that the

locally-hosted version of the documentation looked great, but the version

hosted on GitHub Pages was... not so great. I was seeing a load of text

alignment issues, and also whole bits of text just not appearing at all.

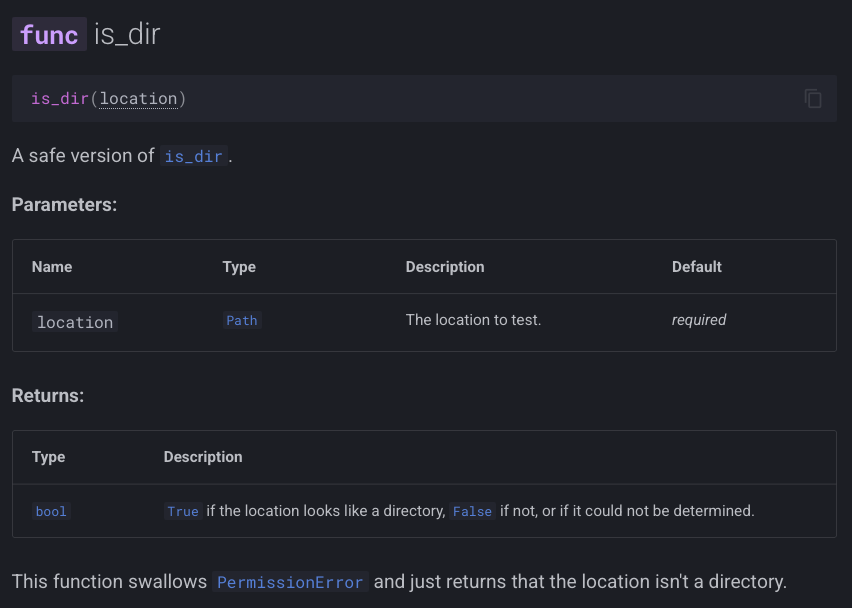

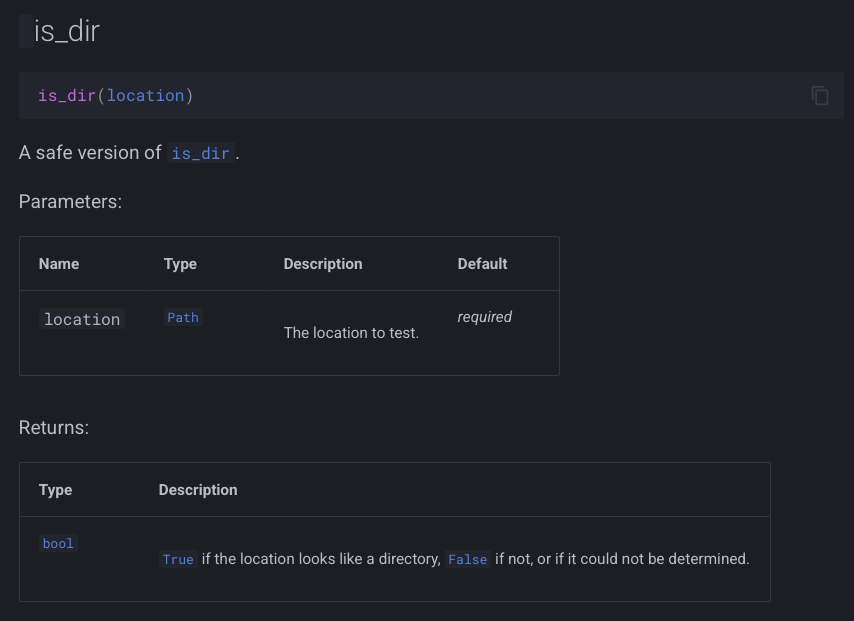

Here's an example of what I was seeing locally:

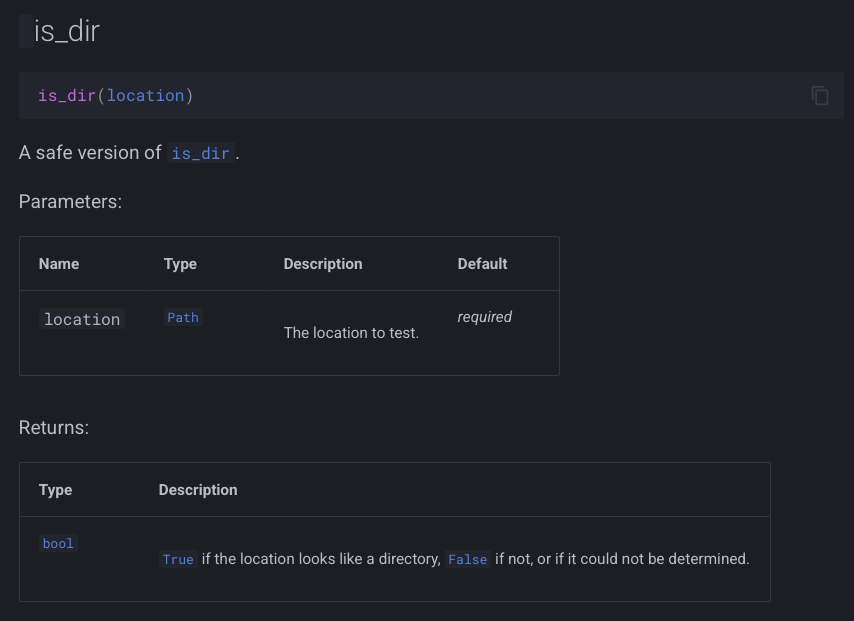

and here's what I was seeing being served up from GitHub Pages:

As you can see, in the "bad" version the func label is missing from the

header, and the Parameters and Returns tables look quite messy.

I spent a little bit of time digging and, looking in Safari's console, I

then noticed that I was getting a 404 on a file called _mkdocstrings.css

in the assets folder. Problem found!

Only... was it though? If I looked in the gh-pages local branch the file

was there (and with fine permissions). If I looked in the remote branch, it

was there too. Thinking it could be some odd browser problem I even tried to

grab the file back from the command line and it came back 404 as well.

At this point it was getting kind of late so I decided I must have screwed

up somehow but I should leave it for the evening and head to bed. Before

doing so though I decided to drop a question into the mkdocstrings

discussions to see if anyone could see where I'd messed

up.

As it turns out, it looked like I hadn't messed up and the reply from the

always super-helpful Timothée was, in effect,

"yeah, that should work fine". At least I wasn't the only one confused.

Fast forward to this morning and, with breakfast and coffee inside me, I

decided to try and methodically get to the bottom of it. I wrote up the

current state of

understanding

and looked at what might be the common cause. The thing that stood out to me

was that this was a file that started with an underscore, so I did a quick

search for "github pages underscore" and right away landed on this

result.

Bingo!

That had to be it!

A little bit of testing later and sure enough, the documentation hosted on

GitHub Pages looked exactly like the locally-hosted version.

So, TIL: by default sites hosted by GitHub Pages will pretend that any asset

that starts with an underscore doesn't exist, unless you have a .nojekyll

in the root of the repository, on the gh-pages branch (or whatever branch

you decide to serve from).

To make this all work I added .nojekyll to

docs/source

and added this to mkdocs.yml:

exclude_docs: |

!.nojekyll

All done!

And now I've worked out a simple workflow for using mkdocs/mkdocstrings

for my own Python projects, in conjunction with GitHub Pages, I guess I'll

start to sprinkle it over other projects too.

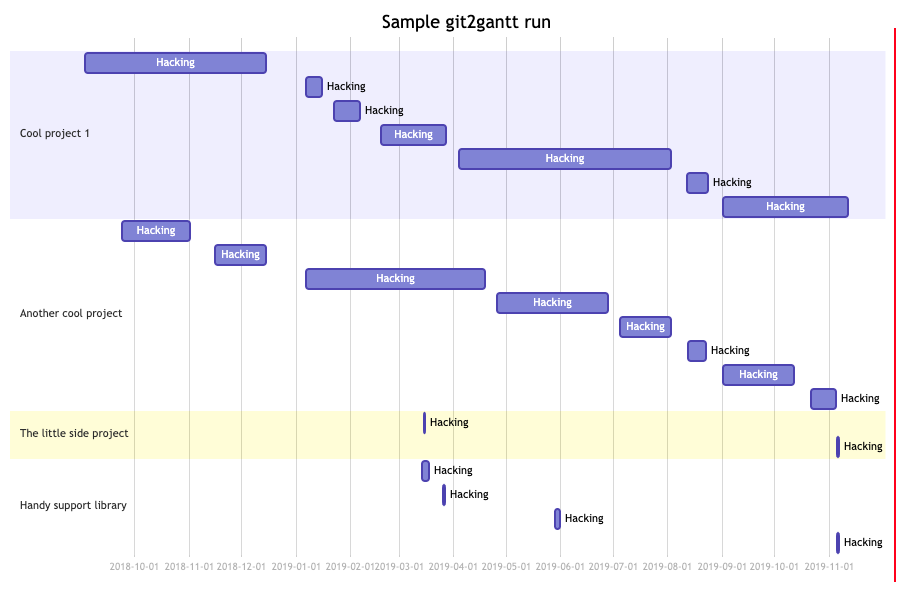

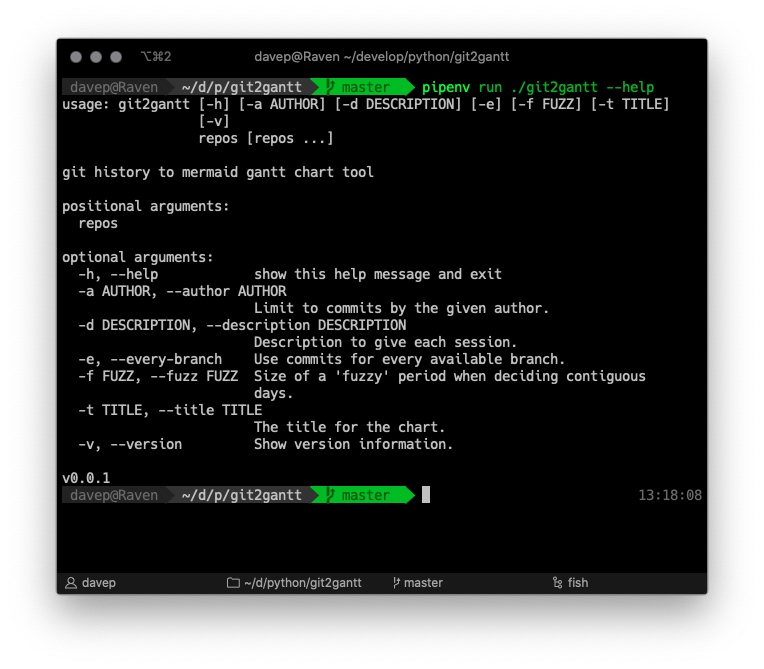

As you can see, it can be run over multiple repos at once, and there's also

an option to have it consider every branch within each repository. Another

handy option is the ability to limit the output to just one author --

perhaps you just want to document what you've done on a repo, not the

contributions of other people.

As you can see, it can be run over multiple repos at once, and there's also

an option to have it consider every branch within each repository. Another

handy option is the ability to limit the output to just one author --

perhaps you just want to document what you've done on a repo, not the

contributions of other people.